Hot Stories

Recent Stories

The Saint Valentine's Day Massacre: How 7 Men Got Lined Up And Killed "Like Dogs" On Lovers' Day

Posted by Samuel on Wed 14th Feb, 2018 - tori.ngThe story has been told of what happened on the day considered to be open of Valentine's most bloody day ever.

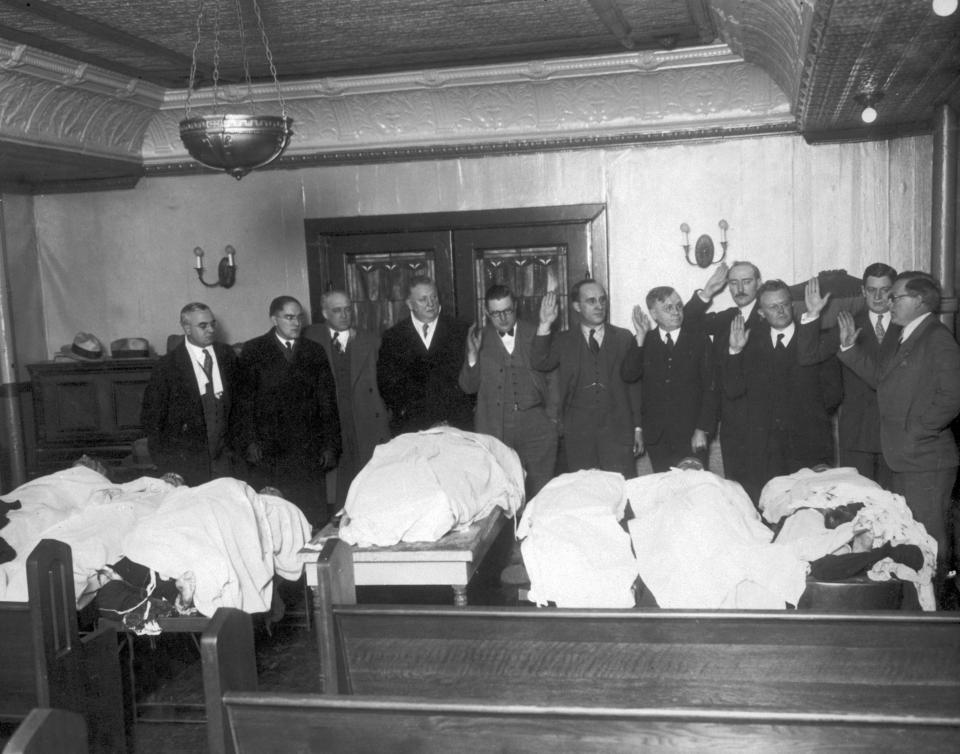

The remains of the murdered men

It wasn't a crime of passion, but the Saint Valentine's Day Massacre remains one of the bloodiest stains on the history of Valentine's day.

On the morning of Valentine’s Day, 1929, a group of men with tommy guns, a 12-gauge and police uniforms stepped out of a black Cadillac. Entering a garage belonging to the SMC Cartage Company at 2212 N. Clark St in Chicago, they lined up against the wall six gangsters and a gambler, blasting them to death, firing squad style.

The newspapers called it a “gang shooting.” A city detective said the men “died like dogs.” The local coroner, Herman N. Bundesen, who had done many things in his life, from educating Chicagoans about syphilis to writing a baby-rearing manual, found himself at the heart of the case.

Working with the police commissioner and state attorney, he empanelled a special jury of six leading businessmen and officials. The evidence they would sift through included bullets embedded in the wall where the men had been shot and the hats that the alleged gangsters had been wearing when they died.

Getting to the bottom of the case was a matter of extreme urgency. To the press and public, the Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre was a sign that gang violence in Prohibition-era (1920-33) America was spiraling out of control. Far from tempering Americans’ habits, all it had done was put cash in the pockets and blood on the hands of men like the 30-year old mob boss many suspected of having ordered the hit: Alphonse Gabriel ‘Al’ Capone.

The men who died on February 14, 1929 were members and associates of the North Side gang, run by George ‘Bugs’ Moran. The North Side gang and Capone’s Chicago Outfit had been vying for some time to control the production and distribution of illegal liquor, and the Valentine’s Day Massacre was apparently planned as an attempt to murder Moran.

Capone himself had a watertight alibi: he was in Florida at the moment the killings took place. But his personal notoriety and the widespread belief that his orders and his men lay behind the massacre led federal prosecutors to pursue a different strategy to bring him down. He was jailed for 11 years in 1931 for tax evasion. No one was ever successfully prosecuted for the murders, but Prohibition—the policy that had done so much to enrich mob bosses like Capone by creating a market for bootlegged booze—was ended in 1933 with the passing of the 21st Amendment

Source: History

Top Stories

Stories from this Category

Recent Stories